Peter Phillips On Gaetano Merola's Ampico recording

Gaetano Merola's 1925 piano roll

Director Edition

(run time ~ 5 minutes)

Gaetano Merola's Ampico piano roll recording

BY PETER PHILLIPS

(read time ~ 6 minutes)

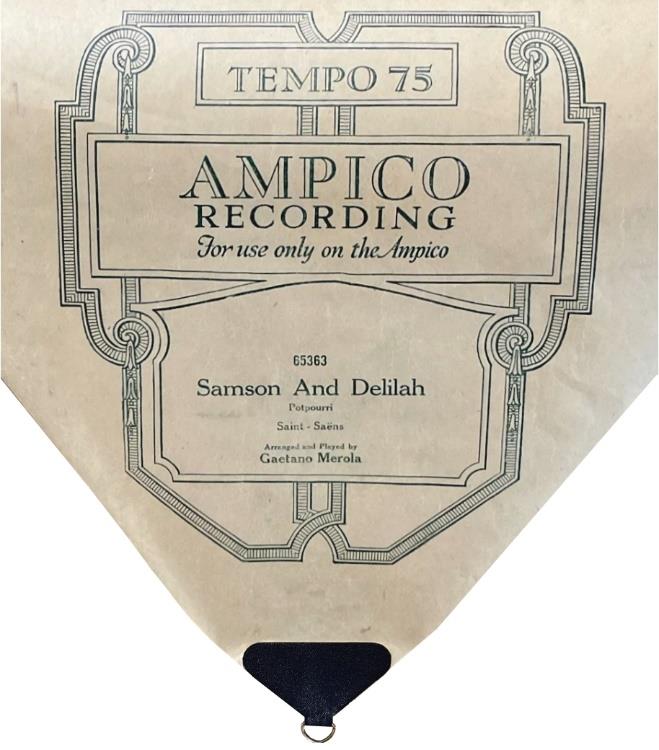

Gaetano Merola is best known as a conductor and the founder of the San Francisco Opera in 1923, but he was also a pianist, a fact proven by his one extant recording: an Ampico piano roll recording of his transcription of selections from the opera Samson et Dalila, by Camille Saint-Saëns. In November 1915, he made a trial recording for the Victor Talking Machine Company in New York of the Franz Lehár song “Thy Heart My Prize” accompanying John Charles Thomas on piano, but the record was never released and is probably lost. This article traces the story of how Merola’s only commercial recording as a pianist might have come about.

Gaetano Merola

Merola was born in Naples in 1879, the son of a violinist at the Royal Court in Naples. He studied piano and conducting at the Conservatorio di San Pietro a Majella in Naples, graduating with honours at the age of 16. He emigrated to the United States at age 18, after being invited to work as assistant to Luigi Mancinelli, a conductor at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. As documented in many sources, he served as a conductor throughout his career in the US, but what of this one recording that he made as a pianist, not on shellac disc, but on a paper roll? We read or hear little about Merola’s pianistic skills, although it is said that his piano studies were to prove invaluable in his career as a conductor and opera impresario.

Piano rolls— the beginnings

The first financially successful instrument to play a piano from a paper roll entered the American market in 1898. Produced by the Aeolian Company and given the name “Pianola” it sat before a piano and played the keys with wooden fingers that were actuated by suction developed by pumping two pedals connected to a set of pneumatics. A similar instrument, called the Phonola, was introduced in Germany at around this time by the Hupfeld company, resulting in arguments about the similarity of the names. These player instruments, called push-ups (or vorsetzer), were immensely popular, giving a new lease of life for the old piano in the parlour. In a few years, companies began installing a player mechanism into pianos, giving the world the player piano.

In 1905, the German company M. Welte and Sons released the world’s first reproducing piano. Unlike the player piano, in which the person operating the player added all musical nuances, the reproducing piano was powered by an electrically-driven vacuum pump and had a complex pneumatic regulating system to control the playing dynamics. Rolls for the instrument were recorded by a pianist playing a piano attached electrically to a means of recording keystrokes and pedalling by scribing lines on a moving sheet of paper. The Welte system also recorded the playing dynamics. Rolls incorporating all this information are now called “reproducing piano rolls” to differentiate them from player piano rolls. Welte called this new instrument the Welte-Mignon, in which the first example had the player mechanism and piano integrated into a stylish cabinet.

The success of this new instrument, despite its expense, spawned an industry that by 1908 saw two competing products to the Welte-Mignon being marketed in Europe. So began a recording industry that attracted many renowned concert pianists to make recordings on reproducing piano roll instead of disc, due to the poor fidelity of acoustic recordings. This success in Europe did not go unnoticed by business people in America.

America and ‘The Ampico’

The first company to produce an American version of the reproducing piano was the American Piano Company, which was formed in June 1908 by three American piano manufacturers—Chickering, Knabe, and Foster-Armstrong—with the aim of increasing sales by entering the emerging reproducing piano and player piano market. It was capitalized to 12 million dollars, about 400 million dollars in today’s money. The company’s reproducing piano was called ‘The Ampico’, designed by Charles Stoddard, with the first model appearing in small numbers in 1911. Rolls for the instrument were initially derived from Hupfeld masters and from player rolls with added expression coding. The Ampico underwent numerous changes, maturing after 1916 as the Stoddard-Ampico, then by 1920 as “The Ampico”, known today as the Ampico A. In March 1914, the Aeolian Company began marketing its reproducing piano called the Duo-Art, intensifying the competition. The Welte-Mignon was also on sale throughout America.

To create a market for a reproducing piano required having roll recordings of renowned artists. In 1919, Sergei Rachmaninoff signed a contract with the American Piano Company that, over the 10 year life of his contract resulted in royalties of over $70,000. Other notable Ampico artists, such as Benno Moiseiwitsch, Josef Lhévinne and Moriz Rosenthal received similar payments, indicating just how successful this industry was. Competition was fierce, and marketing was everything. A popular technique used by the piano roll companies was the “comparison concert”, in which audiences would hear a pianist playing live and then their roll recording of that work. Radio broadcasts of reproducing pianos playing rolls were another method of promoting sales. The status of those recording on roll was also an important marketing strategy.

Conductors and Ampico rolls

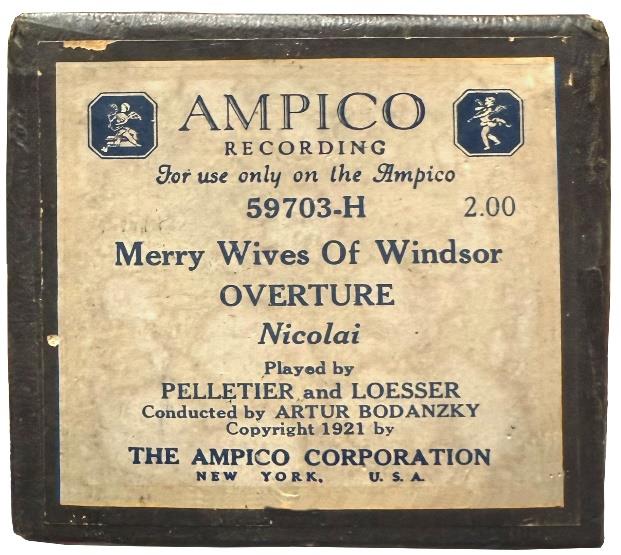

While it was typical that a roll recording artist would be a professional concert pianist, it was not always the case. Conductors, then as now, often had a higher profile than pianists, and piano roll companies were in the business of selling their product. One of the most famous conductors in America at the time was Metropolitan Opera conductor Artur Bodanzky (1877–1939), who was hired by Ampico to conduct duo pianists playing overtures or symphonies. Wilfrid Pelletier (1896–1982), a Canadian conductor and pianist also recorded for Ampico, and as the roll box label shows, Bodanzky conducts Pelletier and pianist Arthur Loesser (1894–1969) playing an overture.

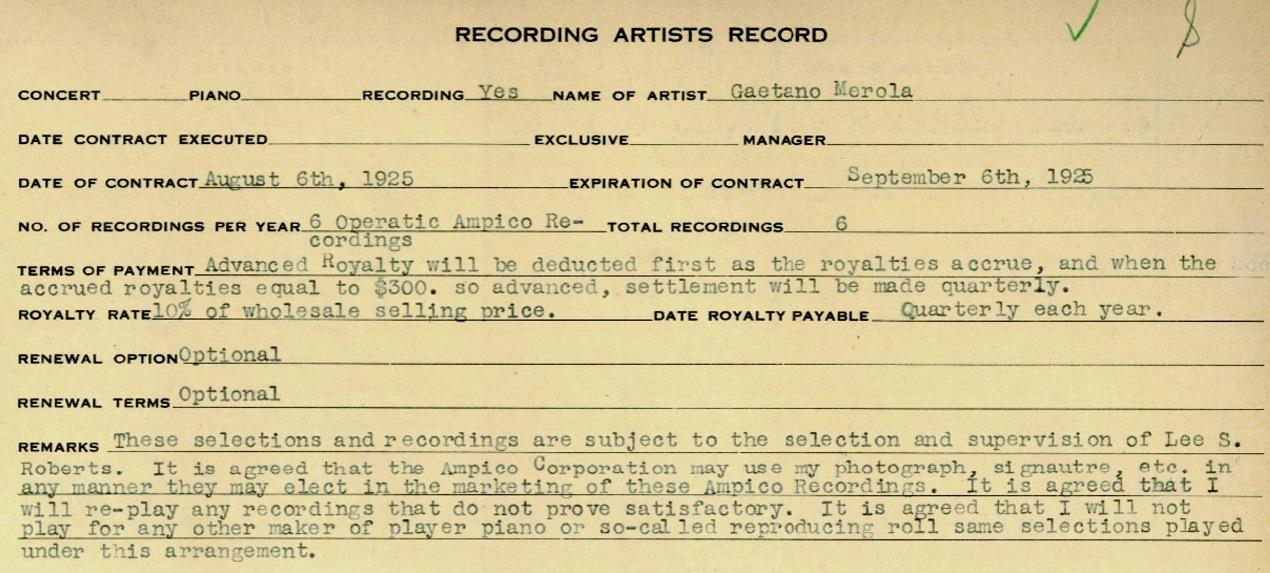

By 1925, Merola was famous enough to attract scouts from the American Piano Company. He signed a contract with the company on August 6th, 1925 to make six Ampico recordings of operatic tunes. As it turned out, he made only one recording and received a total royalty of around $64 over coming years. His Ampico roll was issued in December 1925 and was titled Samson And Delilah Potpourri, a term today that generally refers to a mixture of dried flowers. It is his own transcription of tunes from the opera, and as the audio recording of the roll shows, Merola was, indeed, a fine pianist.

(Peter Phillips began archiving the music on reproducing piano rolls in 1979, and has since archived over 8000 rolls as MIDI files. In 2013, under the supervision of Professor Neal Peres Da Costa he began a PhD at Sydney University, and in 2017 he completed his thesis: Piano Rolls and Contemporary Player Pianos: The Catalogues, Technologies, Archiving and Accessibility. He is currently working with colleagues around the world.)

(Grateful thanks to Peter Phillips for the MIDI file, and to Stanford Libraries Archive of Recorded Sound for use of the image and audio files/licensed via Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International — CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.)