Backstage with Matthew:

The Secret Tricks to Painting the Sky

I am still pinching myself at the level of creativity that is ahead of this year with two major new productions—Parsifal in a continuation of Eun Sun Kim’s journey into the works of Wagner, and then the world premiere of The Monkey King in what promises to be a spectacular addition to the repertory. With new productions come many stories of the creative vitality of a company firing on all cylinders, and I am excited to share these stories with you as we go through the year. I wanted to start with work that has been happening in our scene shop in Burlingame to create the sky backdrop for Parsifal in this new production directed by Matthew Ozawa and with scenic design by Robert Innes Hopkins. It is a stunning new production of this massive epic story, and at the rear of the stage will be a painted sky drop. Painting (vs. projection) allows lighting to capture the nuance of the changing colors, as seen in this rendering of Act III sunrise. I shared the blank canvas in an earlier Backstage with Matthew this year and wanted to share a little of what has gone into creating this drop—it is a wonderful exemplar of the creative talents we are blessed with right here in the Bay Area.

If you’ve not yet had a chance to renew your subscription or become a new subscriber with us, I encourage you to consider this for the 2025-26 season. The kind of creativity we’ll share here is just one example of a hugely vibrant and energized season ahead. Last year we welcomed 1,200 new subscribers to the Opera (an increase of about 10%) and I encourage you to get your tickets while you can—we’re seeing more and more performances selling out!

Over about a ten-day period towards the start of the year, the Opera’s scenic painters took on the creation of this backdrop, present for Acts I and III of the opera. Now you might ask why don’t we just project a sky—isn’t that more efficient? Well, the answer is no both from aesthetic and logistical reasons. Aesthetically, this particular sky effect will work much better as a painted drop—paint can take lighting effects much better, and create a sense of realism and depth not possible with projection. And, because the drop is a static image, not a changing sequence of images (as in our Ring, for example) it is actually more efficient to paint the drop and then have it as part of the scenic elements of the production, not necessitating projection equipment and personnel at every rehearsal and performance.

Here's the kind of visual effect that the sky drop will make possible, taken from a rendering created by designer Robert Innes Hopkins (who also designed our new Tosca and Traviata).

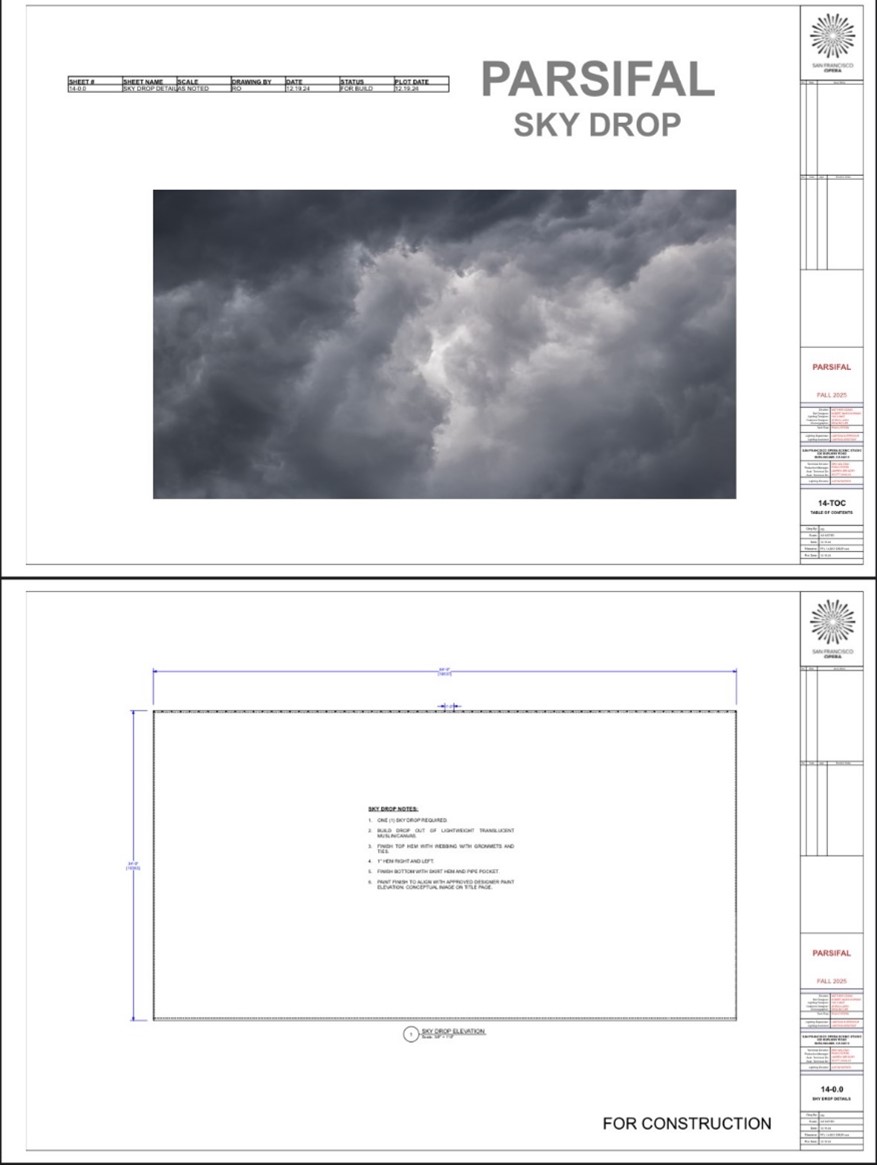

The process for creating a painted drop like this begins with translating Robert’s designs into technical drawings:

Technical drawings for the sky drop.

Scene Shop crew member Victor Sanchez then took a piece of muslin, 40-feet tall and 72-feet wide and hemmed it into a drop 34’ tall and 64’ wide. The drop was laid down on the paint floor of the scene shop, stretched out, and three applications of starch were applied to give the fabric a consistent translucency. The need for translucency is an important part of this particular drop. It will be lit from both in front and behind, and the light areas of the sky are created by the absence of paint, rather than the application of white paint. So the lighter the clouds, the more of the actual muslin you’re seeing. That is different from other painted skies we’ve done in which the lighting all comes from the front and in which the lights come from white paint.) The etherealness of the translucency dictates the painting process below, carried out by Lauren Abrams and Jennifer Bennes, and overseen by our Scenic Artist in Charge, Steve McNally.

Scenic Artist Jennifer Bennes in front of the stretched canvas.

Strips of white paper are then layered over the drop. Outlines of Robert’s cloud design are drawn onto the paper, before the strips of paper are transferred to a “pounce table.” Here the drawn lines are perforated, becoming a series of tiny holes in the paper.

The lines are drawn on strips of paper laid over the blank canvas.

The perforated strips of paper are then returned to the floor, and scenic artists then “pounce” the perforated lines with a fine ground charcoal powder, using this little bag of charcoal dust on the end of a long stick. This transfers the outline to the drop, with the charcoal dust filling the perforated holes and creating the shape of the clouds without actually drawing on the drop.

Scenic artists then use very light spray applications of dye to paint the image, being careful to maintain consistent translucency. As I mentioned above, the lighter areas of the clouds come from the absence of paint, which means that you’re building up layer upon layer of paint, but needing to mask the lighter areas at every turn. This is the reverse of traditional sky painting in which you start with darker paints and then build up the lights in the layers. Here we’re working in reverse, and we do that with…walnut shells!

The walnut shells, ground to a particular size, are laid down on the charcoal outline, and protect the area of the drop that is already at the desired color. In this case, the area of the designer’s image that is the brightest. The walnut shells help ensure the fuzzy edges to the clouds, and can be easily removed once the paint is dry.

Walnut shells laid out for the initial painting of the sky drop.

With each pass of the sprayer, more walnut shells are added, until the darkest areas have been painted.

Once the walnut shells are removed, you see the layering of light and dark areas.

But this is just an in-between part of the process. As more colors and more depth is added, more shells are added in new configurations, and the process of layering the paint continues, always being careful to protect or mask the lighter areas.

This process continues until we get to the final drop – a dramatic, intense, realistic sky scene, 64-feet wide, and ready to be hung and receive light.

Although the walnut shells are not too hard to come by in this walnut-growing capital of the world, we do like to hold onto them and it’s important that they not get thrown away in some over-zealous cleaning!

The painted drop is now completed and in storage in advance of our technical rehearsals in August when it will be hung onstage. Our scene shop does not have a separate paint area, and so it’s important to sequence these large painted drops such that they can alternate with the building work of the more physical scenery which is now well underway for Parsifal. I’ll share this one glimpse of the turntable from mid-February to give you a sense of the scene shop reconfigured to the physical build process headed up by our Shop Foreman John Del Bono, but more on all this to come! From Parsifal we will then head quickly to The Monkey King where a completely different set of creative techniques will be employed.